This blog came out of a conversation with a librarian friend who was talking through the rationale for pushing back against the insistence of some anti-trans lobbyists that their books be stocked on free speech grounds.

Don’t let them draw you onto their turf

The thing about free speech arguments, so beloved of the far right, including those in the “gender critical (GC)” camp, is they only work from within their own, flawed, internal logic. We get firehosed with these arguments almost daily, so we don’t always see the holes. This can make them difficult to contradict, until we realise that free speech is often not the relevant or salient issue in the discussion, and it is not really what is being argued for.

Note, too, that right wing free speech ideology contains a contradiction, which is essentially this:

“What the left are saying is so dangerous and harmful, free speech arguments should not apply – they must be silenced at all costs”.

So, there is an inherent belief that free speech should have limits. The self-same people who claim a right to say what they like about trans people will also talk about “dangerous trans ideology”, social contagion, the need to stop schools from talking supportively about trans kids, and so on.

It’s worth spotting this hypocrisy. Are we really talking about the principles of free speech? Is that really what they are championing? It’s worth a closer look.

A library doesn’t stock all books

This applies to books and libraries, but it also applies to giving people a platform. Because unless a platform or library is equally open to all books/all comers, then there is a selection process. It’s no longer possible to call this a free speech argument if speakers or books are being chosen over other speakers or books. To not be given a place in a library or on a platform is a consequence of selection and choice, not censorship.

And then, a belief that you are owed a place on a platform or in a library becomes a question not of free speech but entitlement.

What’s the selection process by which a speaker is invited to speak? we might ask. What are the criteria, say, if it’s an academic space? A justice-oriented space? A political space? A news program? What credentials does the person need? How is that decided? Does the institution have a responsibility to fact-check before information is included?

Likewise for books: which books are included here? How are they selected? Which books are rejected and why? Are books independently verified and fact-checked?

“A lot of the books we need for our courses aren’t in the library” X*, a trans student tells me when he finds out I’m writing this blog, frustrated that his university library just ordered multiple copies of a GC, explicitly anti-trans book that has been much criticised for misleading and inaccurate content.

Is the anti-trans book required reading for something? Given the general lack of academic rigour behind GC thinking, why would it be? If not, why is it necessary for it to be in the library? Or is the library just including it to come into line with a populist movement targeting trans people? Or for fear of being plastered over the pages of the Daily Mail as an example of the dangerous leftist urge to control discourse?

“How did this particular book meet the rigorous inclusion/selection and peer review processes an academic institution requires in order to maintain academic standards?” is a good question to ask.

Academic rigour

From two decades analysing the flawed logic of “gender critical (GC)” transphobia in particular, I have learned one thing, and that is that GCs regurgitate the same arguments over and over, leaning on the same tiny number of flawed or misrepresented research, all of which has long been superseded and debunked by rigorous academic processes.

What in my experience GCs don’t do is respond to trans academia; the enormous body of research into trans experiences and healthcare, or any of the thorough and rigorously academic data that entirely deconstructs and dismantles their worldview. I have hundreds of relevant academic papers on my hard drive alone – the amount of study and evidence base supporting what I write and train about cannot be understated.

The reason they get away with this lack of academic rigour and engagement without simply being laughed out of the room wherever they go is that trans academia is niche, academics in the field are rarely given a platform to alert the world to good data and arguments, and so it’s possible to maintain public ignorance and for GCs to delude the world that they are making good arguments.

For folks that use the term “critical” a lot, they don’t seem very aware of what it means or what critical academia requires of them.

They are not having an academic discourse because they are not engaging with the vastly superior quantity of academic work that disagrees with them, critically or otherwise. Meanwhile, trans academia has no choice but to discourse with them, and that at least has honed and refined our own feminist arguments to a highly sophisticated level. Which in turn is why trans academia is so respected within feminist academia as a whole.

How do you categorise anti-trans books?

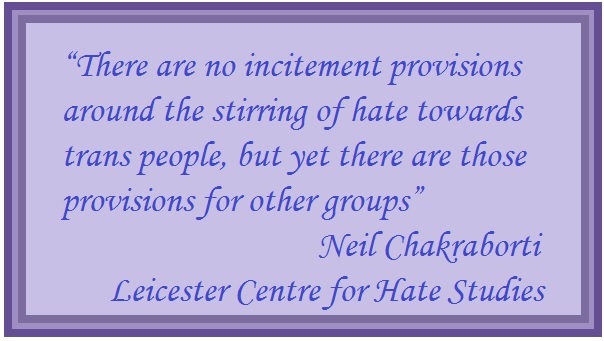

The next question to think about is the one of labelling. Where do you put such books in a library? How do you introduce such speakers? Do you forewarn your audience that, like climate change deniers, GC thinking is disputed by the vast majority of experts in the field? That there is a huge body of work debunking their ideas? That they are widely seen by many as a hate group, organised and well funded lobbyists who disseminate nothing more than propaganda?

Is there a section for propaganda in the library? A section for what is widely considered to be bigotry? Who assesses the material before it is categorised, and how much do they know about the topic? Would you put a book that was widely considered to be homophobic in the LGBTQ+ section? If a book must be in the library, then where should such a book be? Arguably not the LGBTQ+ section if its stance is so profoundly anti part of the LGBTQ community. Equally, these texts cannot be considered categorisable as feminist if their central focus is not on women, but on trans people (and explicitly stripping their civil rights from them). It’s an absurd thought that in 2023, with all the moves forward in discussion of intersectional feminism, that we should be even contemplating a campaign against a marginalised group’s civil rights as “feminist”. Meanwhile, many thinkers, including Judith Butler, have pointed to the ways GC campaigns are damaging to women.

It might be worth also asking this question: In the year 2023, would a library take seriously an academic book about women written by men, and disagreed with by most women? A book about gay people written by straight people, that most gay academics vehemently oppose? What does it mean when we choose not to afford trans people as a group their own voice within academic thought, but allow cis people to pronounce loudly on trans experiences? This could be described as infantilisation.

Of course, if a culture pretends GCs themselves are marginalised, then it legitimises giving them support, facilitating and spreading their views. Which in turn allows people not to lend trans people their support and strength at a time in history when trans people are by all metrics a dangerously beset and scapegoated marginalised group. Cis GCs are not marginalised on the topic of trans issues because they are not trans, whatever their other marginalisations might be. Being widely disagreed with is not in and of itself a marginalisation.

Book burning isn’t what you think it is

Of course, the other thing we know about libraries is they are book burners. I remember as a kid my librarian mother putting me in the back room and getting me to stamp “cancelled” in a pile of books they’d put into retirement. It was the 1970s, but apparently cancel culture was already in full swing. Books get destroyed constantly, because they’re falling apart, because nobody wants them, because the knowledge in them has been superseded, and sometimes, because they are, in light of better understanding about the world and about minorities, too appalling to put on the shelves.

There is nothing a “gender critical” writer has written that hasn’t been superseded, disproven, overturned or thoroughly debunked. They rely on the subject area being sufficiently niche to mean most people don’t know how flimsy their arguments are.

Putting a gender critical book in a library of up-to-date knowledge is akin to having a book from the 70s that says autism is caused by “refrigerator moms” or homosexuality is a psychological disease. There is a need for such books to be held somewhere as a record of what people used to think before we knew better, but again it’s important to think about where, and how they are presented.

At best, it’s like housing the 2nd edition of a science book when we’re now on version ten. No, it doesn’t matter if the copies of the old book are burned, we’re not trying to suppress anything, we’re just keeping up to date. Science is full of things we used to think and now know are wrong. Science is also full of academics who cling to outdated ideas out of ego while the world moves on around them. When they are given undue power and platform, as we’ve seen with the anti-vaxxer movement, they can create havoc.

I sympathise with people who’ve been lured by social media algorithms and firehosed with misinformation and propaganda about trans people, but there are also flat earthers and anti-vaxxers and climate change deniers out there in great numbers, and we don’t hold any moral responsibility to pander to or treat with reverence such beliefs, especially when we’re bound by notions of academic rigour or accurate reporting. An idea being popular or politically expedient does not make it right or hold more academic weight.

The frustrating thing about comparing people who pulp obsolete knowledge or burn their own unwanted books when millions of copies exist in the world is that it misunderstands what Nazi bookburning was.

The Institut für Sexualwissenschaft was specifically a repository of knowledge about LGBTQA+ people, where the openly gay academic and campaigner Magnus Hirschfield formalised (for better and worse) the way trans people were viewed and medicalised in the twentieth century. The Nazis burned the library there and knowledge that was at the time more current and up to date than anything the world had seen was lost entirely.

This is what censorship looks like – the state withholding information from the populace that has not been disproven or superceded, but is objected to on ideological grounds.

in the exact way that GC ideologists go all-out to suppress knowledge of trans issues in schools and the media, and insist that their academically dubious and well disproven dogma is always represented as equally valid in any discussion of trans experiences.

There are appropriate places to put these books

Eventually GC books will be pulped because it’s inevitable that their lack of rigour and coherent argument will be seen through., and nobody will have any use for them, because they are not useful.

Such books need to be preserved in collections that want to hold an accurate history of any movement of thought and ideas. In such collections, e.g of the history of feminist discourse, an insert alerting the reader to issues with the contents is of course appropriate. An institution is allowed to both stock a piece of writing it opposes, and position itself in relation to that writing. But such material only belongs in very specific libraries.

Even there, neutrality in the face of oppression is neither desirable nor required.

My friend tells me about a library that carries accurate transcripts of Hitler’s speeches, which are valuable historical documents, particularly given propaganda rewrote what he said. An appropriate institution can house these works and still have a stance on what it thinks of their contents.

Perhaps, it is more universally understood that Hitler’s speeches are wrong and harmful. We probably won’t have people persuading us that it’s a matter of free speech that copies of these transcripts are stocked in every public library. We don’t have the BBC wheeling out a Hitler expert to justify his philosophy as a counter to every relevant news item.

But how can we possibly be living in a free society if someone is not making a case for Hitler’s views whenever a relevant conversation arises?

If free speech is to be the argument then I’m sorry, it applies as much to Hitler’s speeches as it does to Helen Joyce, Julie Bindel, Kathleen Stock and Sheila Jeffries.

Is this an appropriate place to house this discussion; are we seeking to be a complete and definitive record of a particular branch of knowledge, or are we selective? If selective, then free speech arguments do not apply.

If we are selective, how do we select? My justice principles state we should centre the marginalised group affected by such discourse in advising how we produce a fair and accurate representation of the salient points and issues.

And for those outraged that I’m comparing the ideology of people who currently campaign against trans people’s civil rights with fascism – I could and Judith Butler has, but in this case that’s not the argument I’m making at all. I’m saying that if your argument is “we’re right, we’re good, and we’re not like Hitler” that’s a very different argument than “we, along with everyone else including Hitler, have a right to free speech, therefore you should platform me/stock my books/include my arguments on Newsnight and so on, in exactly the same way as you should include Hitler’s.”

Take this seriously before it’s too late

We’ve seen before the damage done by institutions treating inaccurate, ideological information with more respect, weight and rigour than it deserves, thus giving it an endorsement of robustness it did not warrant. We saw this with the BBC over-platforming Nigel Farage and moving the Overton window strongly in favour of anti-immigrant sentiments that drove the Brexit agenda. We’ve seen it globally with climate change denial being platformed over and over until it is now too late to save much of what would have been saved had the world concertedly and robustly taken climate change seriously when we knew beyond a reasonable doubt that it was a problem.

The trans community are in the heart of a cultural emergency. Those of us who work with large numbers of trans people have a sense of the size of the cost from society unnecessarily wringing its hands over whether it is safe to allow us to exist as who we are.

Libraries, media, and those that are booking speakers can and do have a moral responsibility to ensure they are not signal boosting harmful misinformation, academically obsolete arguments and pure propaganda. Unless it’s their job to ensure that all views are aired and heard equally, and they are making no selection process, the concept of “free speech” is just a red herring.

*name redacted for anonymity

With great thanks to B, my librarian friend, for inspiring this blog, for reading it through, and for providing the following resources for librarians:

![[image: graph of domestic abuse statistics showing disabled people are at higher risk than women as a group]](https://feministchallengingtransphobia.files.wordpress.com/2023/09/dv-disabled.jpg?w=480)

![[image: graph of sexual assault statistics showing disabled people are at higher risk than women as a group]](https://feministchallengingtransphobia.files.wordpress.com/2023/09/dv-disabled2.jpg?w=481)

![[Image: a crying woman cowers in front of a man's clenched fist]](https://feministchallengingtransphobia.files.wordpress.com/2015/04/dv.jpg)

![[image: photo of Audre Lorde speaking, with qotation overlaid "There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle, because we do not lead single-issue lives"]](https://feministchallengingtransphobia.files.wordpress.com/2015/04/lorde-single-issue-wist_info-quote.jpg)

I often spend time reflecting how lucky I am. I think it’s important, reflecting on privilege, being aware of your advantages. I grew up middle class, well educated. I was white. But home was not remotely safe, and school was where I was bullied for being different – traumatised, aspie/ADD, trans, and poorer, more neglected and scruffier than the other kids in my posh school.

I often spend time reflecting how lucky I am. I think it’s important, reflecting on privilege, being aware of your advantages. I grew up middle class, well educated. I was white. But home was not remotely safe, and school was where I was bullied for being different – traumatised, aspie/ADD, trans, and poorer, more neglected and scruffier than the other kids in my posh school.